Associate Professor, Keio University Faculty of Business and Commerce

Shintaro Tomita

Finance (Corporate Finance)

Appointed an Associate Professor in 2020. Holds a PhD in Business and Commerce. Publications include "Underwriting of corporate bonds by bank related underwriter: an analysis of issue prices" (Mita Business Review, 52-6, 2010) and "Conflict of interests for bank's related underwriters: an analysis of underwriting fees of corporate bonds" (Mita Business Review, 54-4, 2011).

Why do businesses use debt?

Associate Professor, Keio University Faculty of Business and Commerce Shintaro Tomita

Capital structure seen from “information asymmetry”

My research area of corporate finance aims to explain various corporate behaviors from a financial perspective. When investing in a business, an enterprise needs to raise the necessary funds somehow. Funds used for investment are called capital. A company chiefly has two types of capital. One is capital raised from shareholders (equity capital), and the other is capital raised from lenders (debt capital). The capital structure describes how the enterprise combines these two types of capital. I study this issue from the perspective of information asymmetry.

Is it reasonable to use debt?

Why do companies use debt in the first place? This is a question that occurred to me while I was learning about the system of stock shares as an undergraduate. Companies need to repay debt but not stocks. Seeing news stories about corporate bankruptcies, it seemed to me that companies should raise funds from stock instead of debt. This question of whether it was reasonable for companies to use debt is at the bottom of my research on capital structures.

In fact, research on corporate capital structures has a very long history. Modern research on the subject is based on the Modigliani–Miller (M&M) theorem, which can be traced back to 1958. They showed that theoretically in an ideal market—that is, a perfect market—capital structure would not impact corporate value. While of course the M&M theorem is a completely logically consistent theorem, it is unrealistic to say that capital structure has no impact on corporate value. This is because real-world capital markets are not perfect markets like those envisioned by the M&M theorem.

Advantages and disadvantages of using debt

For example, in a perfect market bankruptcy is a simple, cost-free event in which ownership of the company transfers from shareholders to lenders. Since lenders would receive what shareholders were denied, the amount received by providers of capital would be the same on the whole. But in the real world, bankruptcy proceedings involve various costs. These costs represent lost value that will not be received by either shareholders or lenders, so they can be considered to decrease total value. Accordingly, use of debt involves the disadvantage of the possibility of bearing costs in the event of a future bankruptcy.

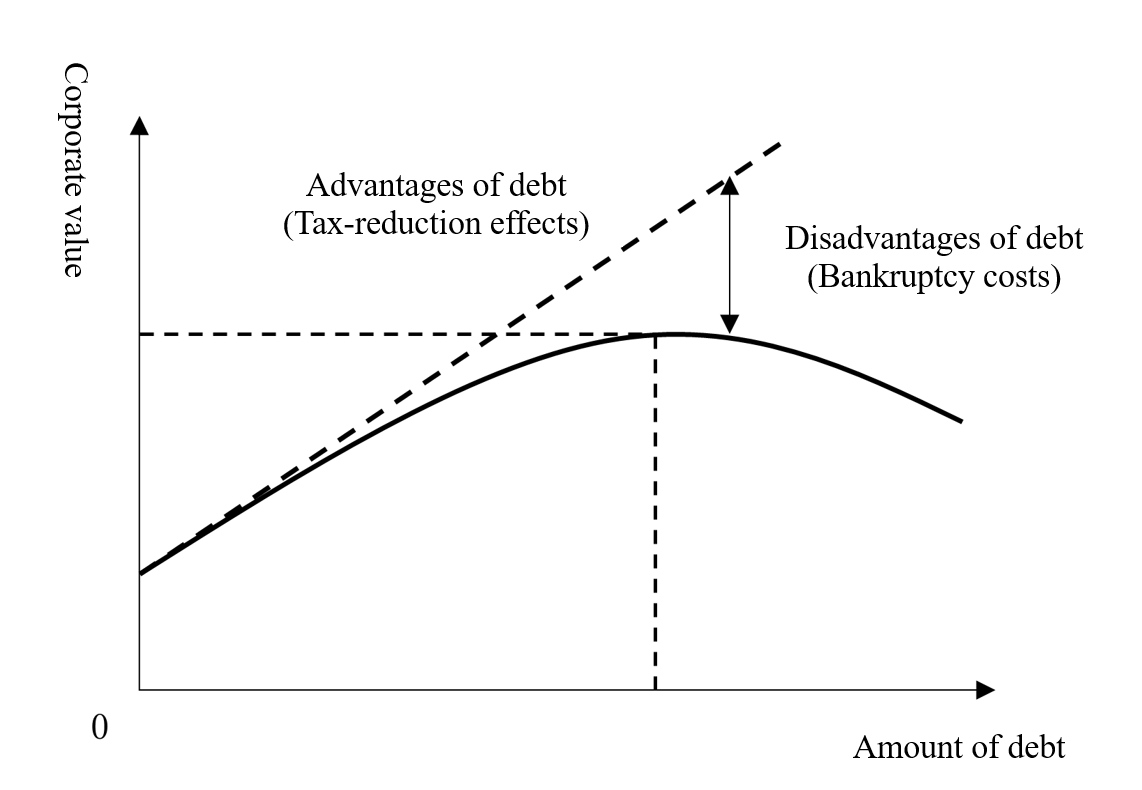

What are the advantages of using debt? On this point, the importance of the tax-reduction effects of debt has been pointed out. In a perfect market there would be no taxes. But the real world includes taxes, and companies need to pay tax on the profit (taxable income) they generate. Since in doing so the interest paid on debt is deducted from taxable income, the more debt a company has the lower will be the taxes it needs to pay. Reducing taxes means that the amount received by providers of capital as a whole will increase, and this can be said to be a clear advantage of using debt.

In this way, research on capital structure has developed through the form of weakening the M&M theorem's assumption of ideal markets. The advantages and disadvantages described above are accepted widely by academics. According to this thinking, as shown in Fig. 1 when a company uses more debt its corporate value will increase as it benefits from tax-reduction effects, but at some level its value will decrease due to the costs associated with bankruptcy. That is, there should be some amount of debt at which corporate value will be maximized.

Debt is used widely by enterprises

The above argument, however, leaves one mystery unsolved. The simplest, most basic mystery concerns the fact that businesses use too little debt. Fig. 2 shows the percentages of companies whose shares are traded on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange that are completely or effectively debt free. Here a completely debt-free company refers to one that has absolutely no interest-bearing debt, while an effectively debt-free one has interest-bearing debt that is less than its liquidity on hand. There is no likelihood that these companies would fall into immediate bankruptcy. Accordingly, they should be able to enjoy the debt advantages of reducing taxes without being overly conscious of debt's disadvantages associated with bankruptcy. As such, it should be beneficial for them to use more debt, but they do not do so. Such companies account for more than one-half of those whose shares are traded on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Prepared by the author using Nikkei NEEDS corporate financial data

Securities trading under conditions of asymmetrical information

I believe that we might be able to explain corporate behaviors such as these by focusing on the presence of information asymmetry in the capital markets. Information asymmetry refers to how corporate insiders will be highly knowledgeable concerning their firm but outside investors will not. Information asymmetry is another element that is not considered in a perfect market. For example, a friend who knows you will might be willing to lend you money, but a complete stranger probably would not. A major reason for this is because of information asymmetry, under which the stranger does not know much about you. It would be even more difficult to engage in such a transaction if the loan was to be paid back at some uncertain time in the future, with the lender having no right to demand repayment. In this way, information asymmetry can be considered to have a strong impact on raising funds through securities such as stock shares, for which there is no promise of future payment.

Numerous previous studies have considered the effects of information asymmetry on capital structure. In particular, it is well known that the presence of information asymmetry leads to additional costs when issuing securities. Under conditions of asymmetrical information, there is no guarantee that the markets will value securities accurately. For this reason, investors who trade in company stock at a discount are likely to oppose issue of new shares to raise funds. This is because the new shares would need to be issued at even lower prices. On the other hand, a company will issue new shares gladly if they are trading at a premium. But investors who notice it are likely to suspect that the company's share price is too high. As a result, its share price will fall if it attempts to issue new shares. This is problematic in that even if the company's shares are trading at an appropriate price, if it attempts to issue new shares then investors will consider its stock price to be too high and it would be forced to issue the shares at a lower price than they should be worth. Such fears and doubt on the part of investors would result in additional costs of issuing shares.

A similar issue arises when repurchasing shares. Even if shares are trading at an appropriate price, if the company attempts to repurchase them then investors are likely to see it as a sign that the shares are trading at a discount and drive the price up. This would make it more costly to repurchase stock, and that is likely to encourage the company to repay its debt before engaging in a costly repurchase of shares. There is a good possibility that such behavior could reduce the company's debt ratio.

New mysteries are the true thrills of research

The above analysis explains only a small part of the realities of the business enterprise. It is hard to explain using this concept why smaller firms are more likely to raise funds through stock than through debt or why some companies use debt to purchase their own stock. An attempt to solve one mystery often leads to another one. Explaining the new mystery can be another perplexing challenge. In a sense, the way it resembles a mystery story, in which one mystery leads to another, may be described as what truly makes research so thrilling.